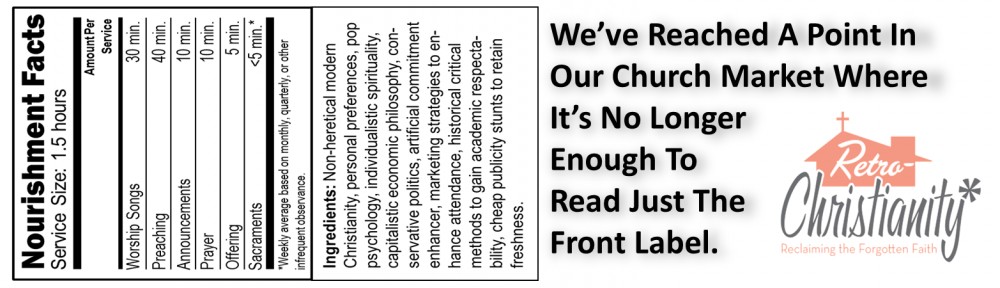

Many corners of the twenty-first century church are drawing on traditional modes of worship, including the use of incense, candles, sacraments, images, creeds, and liturgical prayers. In this respect they’ve sometimes been accused of a “return to Catholicism.” But for most, they have simply gotten fed up with the overly-intellectual worship of evangelicalism. To some believers of my generation, the rigid propositional truths and daunting dogmatism seem to have suppressed authentic spirituality, a vibrant relationship with God, and dynamic, loving relationships with other believers. So, they want a genuine Christian faith free from an oppressive Tradition, but incorporating a variety of “traditions.” This means drawing on non-propositional narratives and symbols that often have an ancient pedigree.

Many corners of the twenty-first century church are drawing on traditional modes of worship, including the use of incense, candles, sacraments, images, creeds, and liturgical prayers. In this respect they’ve sometimes been accused of a “return to Catholicism.” But for most, they have simply gotten fed up with the overly-intellectual worship of evangelicalism. To some believers of my generation, the rigid propositional truths and daunting dogmatism seem to have suppressed authentic spirituality, a vibrant relationship with God, and dynamic, loving relationships with other believers. So, they want a genuine Christian faith free from an oppressive Tradition, but incorporating a variety of “traditions.” This means drawing on non-propositional narratives and symbols that often have an ancient pedigree.

But this is extremely difficult to do well. And to date, I’ve not seen it rise above the level of mediocre.

I find the buffet-style traditionalism characteristic of many new churches to be a little, well, silly . . . or at least juvenile. I have nothing against incense and candles. But picking and choosing which “traditions” from two thousand years of church history to use in today’s worship seems a little ridiculous if we detach them from the history, culture, and theology in which they originally developed. Some things just don’t fit. If I bought a high-end piece of antique furniture from an estate sale and placed it in my living room, it would look silly. In the same way, I’ve seen evangelicals try to incorporate ancient rites and rituals into their worship in ways that make me cringe.

Labyrinths, prayers of the saints, stations of the cross, and other practices associated with Roman Catholicism or eastern catholic mysticism enjoy a new audience among some Christians seeking a different type of spiritual devotion—a deep, authentic, meaningful Christian experience. But I see very little sense of theological coherence, a clear notion of what is central, how these things fit together, the stories they try to tell. Let’s set aside the whole question of epistemology and propositional truth for a moment. When Christians try to weave together premodern practices like these, they often apply very modernistic anthropocentric criteria of individual preference. However, the new drive for community authenticity is not much different than the by-gone quest for personal certainty: in the end my personal reason or emotions reign.

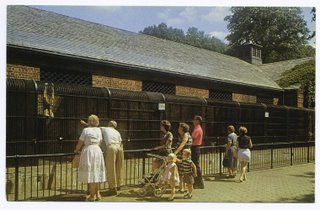

The result of harvesting “traditions” from church history is not much more appealing to me than the old-style zoo that zoological societies have tried to replace over the last several decades. Remember when we used to rip God’s creatures from their natural habitats and cram them into rows and rows of jail cells for spectators to “enjoy.” In many ways today’s rip-off of ancient traditions is worse. Some have gone on a “Bring ’Em Back Alive” safari, snared a handful of appealing practices from the jungles of church history, killed them, and now display them in their two-year-old churches like disparate plush toys spread over a toddler’s bed.

I like tradition. I like it a lot.

But I don’t like watching people mishandle it.

Please stop.