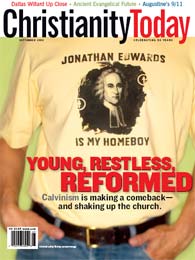

The September, 2006 cover of Christianity Today pictures a young adult in a tee shirt with an image of early American Congregationalist pastor, theologian, and evangelist, Jonathan Edwards. In a distinct, postmodern font, the shirt says, “Jonathan Edwards is my homeboy.” The cover of the magazine reads, “Young, Restless, Reformed. Calvinism is making a comeback—and shaking up the church.”

The September, 2006 cover of Christianity Today pictures a young adult in a tee shirt with an image of early American Congregationalist pastor, theologian, and evangelist, Jonathan Edwards. In a distinct, postmodern font, the shirt says, “Jonathan Edwards is my homeboy.” The cover of the magazine reads, “Young, Restless, Reformed. Calvinism is making a comeback—and shaking up the church.”

In my own life and ministry, I can confirm that Calvinism is making a comeback . . . as well as a renewed interest in theology and church history in general. The seeker-sensitive, mega-church trend of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s is, I believe, fading into its twilight. Younger generations of both believers and theologians are embracing an evangelical theology that taps into its historical roots and draws generously from the deep doctrinal wells of the community of faith—both past and present. The resurgence in Calvinism is part of this trend.

What, exactly, is Calvinism? What does it mean to be “Reformed”? Is it the same as Covenant theology? Is it a good thing or a bad thing? Does it matter?

The Road (Back) to the Reformation

When I was a high school student at a secular school, I learned only two things about John Calvin (1509–1564)—the father of Calvinist theology: 1) he believed people were predestined for hell, and 2) he burned Michael Servetus at the stake. When I became a Christian and attended Philadelphia College of Bible, I actually read Calvin (and Michael Servetus!) and I realized that he had been unfairly caricatured and demonized . . . even by Christians. And in one of my doctrine classes with Charles Ryrie I slowly became convinced of the key Calvinist doctrines. My own awakening into Calvinism was a gradual process of unlearning and relearning, coming to terms with what the Bible actually says (not what I wish it said) about issues like free will, sin and guilt, grace, faith, predestination, and all these major issues that distinguish Roman Catholic from Protestant theology. I began to believe that evangelical theology that rejected Calvinism was unwittingly stumbling into the murky swampland of medieval Roman Catholic salvation—the idea that we cooperate with God to be saved.

In the end, I embraced Calvinism as the best expression of the theology of the reformation and the most biblically-faithful explanation of the doctrine of salvation. So, in a large part, I am personally part of the resurgence of Calvinism that Christianity Today was describing. (But, no, Jonathan Edwards is not my homeboy.)

This often comes as a shock to those who, like me, were raised thinking that Calvinism violates free will, that it relieves Christians of the responsibility for missions, that it predestines people to hell, and that it requires you to believe in amillennialism, infant baptism, and allegorical interpretations of Scripture. None of these things are true, and foolish statements like these are best left unsaid. A professor at Philadelphia College of Bible convinced me that a person can hold to the Calvinist or “Reformed” doctrine of salvation while also embracing a Baptist view of the church and a premillennial, dispensational view of the end times. There have always been Calvinist Baptists, Calvinist Prebysterians, and Calvinist Congregationalists.

So, we need to realize that the recent upsurge in Calvinism is not a “take-over” by a hostile heresy or attack by dangerous doctrines. Both Dallas Seminary and my local church home, Scofield Memorial Church, have deep historical roots in American Calvinist theology. In fact, one could make a case that a rejection of Calvinism over the last several decades reflects a deviation from the original, rich theological soil of our Bible Church tradition.

Calvinism Clarified

So, what do Calvinists actually believe?

Through the centuries, Reformed theology has communicated its essential doctrines with five “points” summarized by the acrostic, “TULIP.” These are: Total depravity, Unconditional election, Limited atonement, Irresistible grace, and Perseverance of the saints.

Because of the fall, the human mind, emotions, and will are totally depraved—lost and unable to respond to God’s salvation without His quickening Spirit giving us the ability to believe (Romans 3:9–10; 8:7–8). If all human beings throughout history are lost and already condemned, and if God must act first to save anybody, then God must choose to save those who are saved (Acts 13:48; Romans 9; Ephesians 1:3–6). He thus elects those He will save unconditionally, not based on anything they have done or will do. Next, the controversial doctrine of limited atonement does not teach that Christ’s blood is insufficient to pay for all sins, but that in the purpose of God’s election, Christ died only for the eternal benefit of the Church (see Ephesians 5:25–27). Because God chose who will be saved, all of the elect will come to believe through the prayers and preaching of believers, and no non-elect will accidentally believe. God’s grace for those whose mind is illuminated is irresistible (John 6:44; 10:27; Acts 2:39; Romans 8:29–30). Finally, those that God elected, called, and saved by grace through faith can never lose their salvation. True saints will persevere in faith until the end and are therefore saved eternally (John 10:27–29; Romans 8:29–39; Ephesians 2:8–10).

This five-point doctrine of salvation represents the essence of “Calvinist” or “Reformed” theology. It also represents several distinguishing marks of Protestant versus Catholic views of salvation and taps into the roots of our own conservative, fundamentalist, and even dispensationalist heritage, regardless of the drifts and deviations of the past several generations.

Whether or not you agree with Reformed theology, in light of its recent revival and resurgence believers ought to at least be aware of what Calvinism really is—and is not. And, as always, we must consult the Scriptures before either embracing or dismissing current trends in theology.