Back in 2004, I presented a very long (71-page) paper at the Evangelical Theological Society entitled, “Power in Unity, Diversity in Rank: Subordination and the Trinity in the Fathers of the Early Church.” This paper was the result of research I conducted related to my PhD studies in patristics. In light of recent discussions among evangelicals regarding the issue of subordination and intra-trinitarian relationships, I thought I would make this paper available. It is an exhaustive (some might say, exhausting) analysis of every instance in which the relationships between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are even mentioned in the orthodox writings between Didache and Irenaeus. The full paper can be found here as a PDF. Because it was written in 2004, it is clearly not up-to-date in its secondary literature, but my hope is that interested readers will find the primary source data (all included in a lengthy appendix) to be helpful.

Below, I include the excerpt from the paper that summarizes my conclusions and implications based on the work of these early fathers. I would ask that readers first review the analysis of the entire paper before interacting with my conclusions.

Excerpt from Michael J. Svigel, “Power in Unity, Diversity in Rank: Subordination and the Trinity in the Fathers of the Early Church,” a Paper Presented at the 56th Annual Meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, November 18, 2004, San Antonio, Texas.

Conclusions

Based on the preceding analyses, we can make the following conclusions regarding the relationships of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in the writings of the earliest fathers.

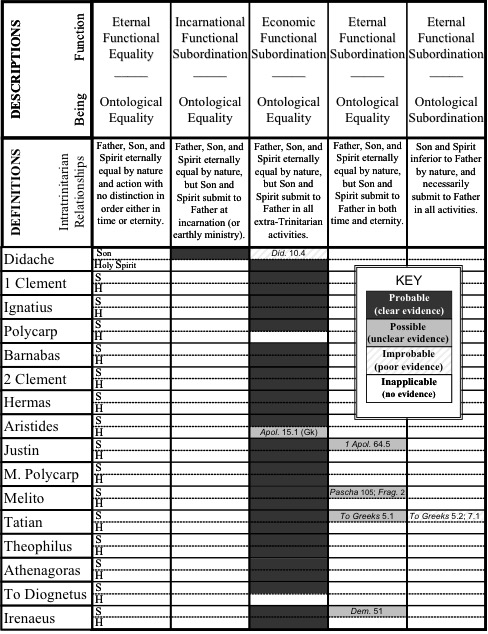

No Clear Arian Ontological Subordination. There is no clear example of an Arian ontological subordinationism in which the Son is a created being or has an inferior divinity to the Father, though Tatian’s concept of the Logos may come close. When their language was clear, the early fathers’ concept of subordination was functional, not ontological. LaCugna rightly stated that “we should not regard this economic subordinationism as heretical or even as an inferior or incoherent Christian theology of God and Christ.”[1] Rather, just the opposite is true: where there was opportunity given by the context, Christ was called “God,” “eternal,” or the essential mediator of the Father’s will.

No Functional Egalitarianism. There is no discernible tradition whatsoever of what is today described as ontological and functional equality or a “communitarian” or “democratic” model of the Trinity. Nor is there clear evidence of a view which states that the persons of the Godhead could have agreed to take on different roles than what has unfolded in the economy of creation (e.g. that the Father could have become incarnate or the Son could have indwelled believers rather than the Holy Spirit).

Ontological Equality and Functional Subordination. There is an overwhelming tradition of what is today described as ontological equality and functional subordination within the Trinity that emphasizes the monarchia of the Father. While the Son and Spirit are not creatures, the Father is their head, meaning that all activities conform to his will.

Possible Drift toward Ontological Subordinationism. While the later second century fathers began to speculate more on the specific nature of the generation of the Son,[2] we begin to discern language implying an eternal functional subordination while still maintaining essential (ontological) equality. However, with Tatian the language becomes fuzzy, and the stage appears to be set for greater deviation away from ontological equality toward Arian ontological subordinationism.

Implications

If, for the sake of argument, we were to regard the fathers of the first and second centuries as our canon of orthodoxy and the proper understanding of Scripture, then our judgments on various views of subordination and the Trinity become rather clear.

Eternal Functional Equality and Ontological Equality. Modern day advocates of what I call “eternal functional equality” suggest that “there can be no separation between the being and the acts of God, between the one divine nature of the three persons and their functions.”[3] Therefore, orthodox ontological equality is said to demand functional equality as well, and distinctions in rank between the Father, Son, and Spirit are rejected. Instead, the Father, Son, and Spirit are regarded as functioning in a co-equal fellowship, with one mind and will. Though each member of the Triune community performs distinct activities, these activities are not ordered in rank or hierarchy.[4] Instead of the Son and Spirit functioning in submission to the Father, the three persons are said to function in mutual submission to each other. In light of this study, the problem with such a view is that no extant Christian writings of the first and second centuries suggest anything remotely close to such a model, but rather consistently present the Father as the head and the Son and Spirit as functioning in submission to the Father.

Incarnational Functional Subordination and Ontological Equality. Advocates of a temporary or voluntary subordination of the Son to the Father limit the submission of the Son to the time of his earthly ministry or commencing with the incarnation. Thus, the Son’s role of submission to God is a result of his taking on full human nature and living in obedience to the law. However, in light of the early fathers, limiting the functional subordination of the Son to the incarnation would be too narrow. In the first and second century writers, the Son and Spirit consistently submit to the Father’s will, even prior to the Son’s incarnation and Spirit’s sending into the world. Also, such a view of incarnational subordination does not explain why the Holy Spirit is presented by the fathers as functioning in submission to the will of the Father without having become incarnate.

Eternal Functional Subordination and Ontological Equality. If we were to employ first and second century Christian teaching as a standard, the advocates of an eternal functional subordination of the Son to the Father would have little clear evidence to support their view. The descriptions of the relationships between Father, Son, and Spirit in the early fathers refer to activities of the Godhead in relation to the created order. Apart from actual activities in creation, the nature of the relationships is vague. This does not preclude the existence of an ordered relationship based on fatherhood, sonship, and spiration, but the actual evidence is minimal and unclear. In this sense, complaints against the language of “eternal functional subordination” seem to be valid, and evangelicals should probably cease using such terms.[5]

Economic Functional Subordination and Ontological Equality.[6] The view of the earliest post-apostolic fathers is best described as one in which Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-eternal and co-equal with regard to deity and power, but in extra-Trinitarian actions the Father is the head, the Son is the mediator, and the Spirit is the pervasive active presence of God. While we cannot logically project this economic functional subordination into an eternal state apart from creation, this taxis would be consistent with the interpersonal relationships implied by the names “Father,” “Son,” and “Spirit.”

Eternal Functional Subordination and Ontological Subordination. The fathers’ consistent subordination of the Son to the Father in their will and works has sometimes been mistaken for an ontological subordination relegating either the Son or the Spirit to the realm of finite creation rather than eternal deity. For example, in his polemic against Trinitarianism in favor of Unitarianism, Stannus, citing Polycarp’s prayer on the pyre as evidence of non-trinitarianism in the second century, writes, “The ante-Nicene fathers invariably spoke of Christ as subordinate to the Father.”[7] Although he is correct in this assertion, his conclusion that this necessarily implies an inequality of divinity is an unfounded exaggeration. His error is similar to that of modern assertions that subordination in function necessarily means inequality of eternal nature. Where the early fathers are not silent, they illustrate that one can hold simultaneously to both functional subordination and ontological equality of being. Therefore, attempts by groups such as Jehovah’s Witnesses who seek sympathetic theology in the early fathers are misguided.[8]

Two Final Questions

Does Economic Functional Subordination Prescribe a Particular Social Order? The ordering of ecclesiastical leadership suggested in 1 Clement and stated explicitly and repeatedly in the Letters of Ignatius was not tied to an eternal role in the Godhead, but to the sending of the Son in the economy of salvation. This ordering is independent of questions regarding the eternal relationships between Father, Son, and Spirit. In the context of contemporary egalitarian and complementarian debates—whether in the home, government, society, or church—the debate concerning eternal functional subordination is irrelevant as far as the early fathers are concerned. There appears to have been enough justification for ecclesiastical ordering in the simple fact that the Son was sent into the world. However, we must recognize that the fathers do not extend this divine ordering beyond that of ecclesiastical structures. Although 1 Clement addressed the issue of God’s establishment of human government on earth to which all men are to submit, he linked such authority to his divine decree, not to a Trinitarian model (1 Clem. 61:1). However, one could suggest that the ways in which God orders society in general should be consistent with his work. In short, functional subordination in the Trinity need not be eternal to serve as a basis for social structures, but this type of application of Trinitarian theology outside church order is not found in the early fathers.

Are the Early Fathers “Orthodox” or “Heretical”?[9] Based on an exhaustive analysis of the primary evidence summarized in this paper, the fathers’ teaching can be summed up in Athenagoras’s statement, “power in unity, diversity in rank.” For a moment, allow me a brief fit of rhetoric. Those who want to define historical orthodoxy as discerning no functional distinction in rank between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are forced into one of three solutions with regard to the first and second century fathers. They must either a) anathematize the early fathers as heretics; b) twist their writings to conform to an egalitarian standard; or c) simply ignore them. It appears that most have chosen the final option. I reject this move. Instead, I believe we ought to embrace the early fathers as a solid, though developing, orthodox link in the chain of Trinitarian tradition handed down from the apostles in Scripture, subsequently taught by catechesis and liturgy, and guided in its growth and development by the teaching ministry of the Holy Spirit. If this is the case, orthodoxy must not only grudgingly accept the concept of ontological equality and functional subordination as merely an acceptable option, but perhaps it should cheerfully embrace it as most accurately reflecting the faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) and handed down to “faithful men” who were “able to teach others also” (2 Tim 2:2).

Visual Summary of Evidence

[1] LaCugna, God for Us, 26.

[2] This may have been the impetus for Irenaeus to assert that the generation of the Son is unknowable (A.H. 2.28.6).

[3] Giles, The Trinity and Subordinationism, 93.

[4] Ibid., 92–96.

[5] In my current thinking on this matter, the second century fathers’ adamant insistence on the utter distinction of Creator and creature, with the latter a creation ex nihilo, makes the notion of eternal functional subordination a problematic description. Subordination or submission to the will of the Father implies some sort of activity or function. Without a creation in which and toward which such actions are aimed, can we really speak about “subordination?” Unless we argue for a subordination of essential nature, we cannot speak of subordination in a timeless, eternal state. My view, of course, assumes a notion of creation ex nihilo. However, if one advances a doctrine of God and time that includes God’s “own time” or some pre-creational activity, then the term “eternal functional subordination” could be a legitimate category. On historical and contemporary issues of God, time, and creation, see William Lane Craig, God, Time, and Eternity—The Coherence of Theism II: Eternity (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2001).

[6] My use of the term “economic” here refers to any divine activity in the economy of creation. That is, in all extra-Trinitarian works of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It does not apply to whatever inconceivable and unknowable relationship the Father, Son, and Spirit had in their existence apart from creation.

[7] Stannus, Doctrine of the Trinity, 28.

[8] Cf. for example, Greg Stafford, Jehovah’s Witnesses Defended: An Answer to Scholars and Critics, 2d ed. (Huntington Beach, CA: Elihu, 2000), 215.

[9] This assumes, of course, that we can meaningfully use these terms in their normal sense with reference to the early fathers who precede the ecumenical councils of the fourth and fifth centuries. While historians shy away from them, evangelicals may use these terms because of their belief in a transcendent standard of doctrinal truth against which teachings of every age can be measured.