Soon Bethany House (a division of Baker Publishing Group) will begin releasing a trilogy of mini-theologies entitled Exploring Christian Theology edited by Dr. Nathan Holsteen and me, with significant contributions by our colleagues in the theological studies department of Dallas Theological Seminary: Dr. Douglas Blount, Dr. Scott Horrell, Dr. Lanier Burns, and Dr. Glenn Kreider. We’re starting with what is actually the third volume in the series (The Church, Spiritual Growth, and the End Times), then releasing volumes 1 and 2 in the next couple of years.

Soon Bethany House (a division of Baker Publishing Group) will begin releasing a trilogy of mini-theologies entitled Exploring Christian Theology edited by Dr. Nathan Holsteen and me, with significant contributions by our colleagues in the theological studies department of Dallas Theological Seminary: Dr. Douglas Blount, Dr. Scott Horrell, Dr. Lanier Burns, and Dr. Glenn Kreider. We’re starting with what is actually the third volume in the series (The Church, Spiritual Growth, and the End Times), then releasing volumes 1 and 2 in the next couple of years.

But wait a second . . . Why another “systematic theology” when the market is flooded with them? To answer this question, let me say that ECT is not another systematic theology. In fact, I can honestly say that this series is something completely different.

Let me explain.

Like any good introduction to evangelical theology, the three volumes in ECT will present believers with much-needed introductions, overviews, and reviews of key tenets of orthodox protestant evangelical theology without getting bogged down in confusing details or distracted by mean, campy debates. These three simple and succinct books will provide accessible and convenient summaries of major themes of evangelical Christian doctrine, reorienting believers to the essential truths of the classic faith while providing vital guidebooks for a theologically illiterate church.

But isn’t that what every entry-level theological intro promises? Yes, but let give you six reasons Exploring Christian Theology really is completely different.

First, we wrote Exploring Christian Theology for a genuinely inter-denominational evangelical audience. And when we say “inter-denominational,” we don’t mean that we’re trying to get conservative Lutherans, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Anglicans, and Charismatics to read our theology in order to persuade them to leave their branch of evangelicalism and climb onto ours. Not at all! Instead, we’re descriptively presenting the whole tree of evangelical orthodoxy—as dispassionately and positively as possible. This means pastors, teachers, students, lay-leaders, new believers, and mature saints of every orthodox protestant evangelical church can use these volumes without feeling like they have to constantly counter our assertions with their own views on the matter. Simply put, we’re so interdenominational that if a reader doesn’t agree with our central assertions, they’re probably not orthodox, protestant, or evangelical.

Second, the style of this series will be genuinely popular, informal, and accessible. Sometimes extremely so. Think contractions . . . illustrations . . . alliteration. You’ll see generous bullet points, charts, and graphs instead of just walls of impenetrably dense text on every page. Brace yourself for the pace of a hockey game rather than a golf tournament (sorry, golfers, but . . . YAWN). We wrote this for people who don’t necessarily carry around a large arsenal of biblical, theological, and historical facts in a side holster.

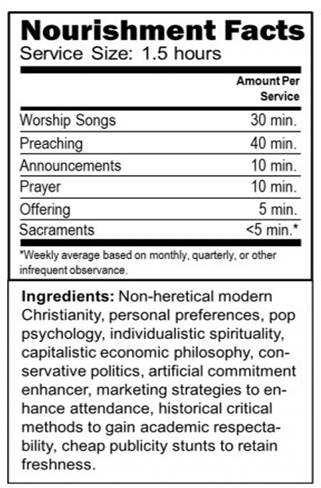

Third, you’ll find this series to be worth every penny you spend on it and, more importantly, every minute you spend reading it. Let’s face it, some mini-theologies with a broad appeal are just fancy-wrapped junk food with very little spiritually nutritional value. Yes, these volumes are intended to be “stepping stools” to the bottom shelf—brief, succinct summaries of specific areas of doctrine that can each be read quickly, consulted easily, and grasped by anybody. But at the same time you’ll find them to be comprehensive, thorough, careful, and—if you bother to explore the endnotes—well-researched and documented.

Fourth, this is a community-authored theology. Rather than presenting the perspectives and opinions of an individual teacher, tradition, or denomination, Exploring Christian Theology is planned, written, and edited by several theologians who are experts in their various fields. We hold each other accountable to avoid personal hobby horses, pet peeves, and doctrinal idiosyncrasies. In other words, you’ll never get one man’s opinion about this or that doctrine. Instead, you’ll get a clear explanation of the classic orthodox, protestant, evangelical consensus and a dispassionate presentation of points of allowable disagreement and diversity within evangelicalism. As such, these handbooks can be confidently used for discipleship, catechesis, membership training, preview or review of doctrine, or personal quick reference by any orthodox, protestant, evangelical church or Christian.

Fifth, these volumes will serve as a foyer into a broader and deeper study of the Christian tradition. We didn’t design Exploring Christian Theology to compete with other systematic theologies in the marketplace. There are a lot of great ones out there—some reflecting the views of certain confessions or traditions, others the perspectives of specific teachers or preachers. Our volumes are designed to supplement (not supplant) more detailed systematic theologies . . . to complement (not compete with) intermediate and advanced works. We promise that after thumbing through ECT, you’ll be much better prepared to read more advanced systematic theologies with informed discernment and a firm grasp on central tenets as well as an understanding of ancillary discussions.

Finally, there are unique features in Exploring Christian Theology you’ll have a hard time finding all together anywhere else. Right up front we present a high altitude survey of the doctrine in order to set forth the unity of the faith among numerous diverse evangelical traditions. Then you’ll find no-nonsense discussions of key Scripture passages related to that volume’s specific areas of theology. You’ll also find a very helpful narrative of the history of the doctrine throughout the patristic, medieval, reformation, and modern eras. We also provide a glossary of important terms related to the doctrines as well as a feature called “Shelf Space” with recommended resources for probing deeper. By the end of each part of the volume dedicated to a particular area of doctrine, you’ll be warned about the most prominent false teachings related to the doctrine and encouraged with practical application points flowing from a right understanding of the doctrine. Besides all this and more, I’ve been told that the generous first-hand quotations from church fathers, theologians, scholars, reformers, pastors, and teachers from the whole span of church history is worth the entire volume.

In short, Exploring Christian Theology is not my theology, but our theology—the theology of the orthodox, protestant, evangelical tradition. It’s presented in a winsome (and sometimes whimsical) way. It balances biblical, theological, historical, and practical perspectives. And it’s written with the whole evangelical tradition in view.

You can pre-order Exploring Christian Theology today from these sellers: