For many churches and denominations, it would be unthinkable that a believer who has not been baptized as a mark of initiation into the covenant community would be invited to partake of the covenant community’s most intimate observance, the Lord’s Supper (or “eucharist,” “communion,” or “Lord’s Table”). Usually such churches initiate their members at a young age, if not in infancy, or they have a fairly high view of baptism and its role not only as a public profession of personal faith but also as a rite of initiation into the community of the faithful.

For many churches and denominations, it would be unthinkable that a believer who has not been baptized as a mark of initiation into the covenant community would be invited to partake of the covenant community’s most intimate observance, the Lord’s Supper (or “eucharist,” “communion,” or “Lord’s Table”). Usually such churches initiate their members at a young age, if not in infancy, or they have a fairly high view of baptism and its role not only as a public profession of personal faith but also as a rite of initiation into the community of the faithful.

However, many other churches—usually of the independent evangelical “Bible-church” variety—have hardly considered the question. Many believers in those churches would be surprised that this even is a question. These congregations often practice communion in a way that makes it open to anybody who professes faith in Christ—even if it’s a quiet, invisible, personal, and sudden faith in response to the message just preached. It becomes, as it were, a point of personal devotion and reflection, unconnected to the person’s relationship with the covenanted community and body of Christ through the act of baptism.

In the following, I will make a biblical-theological and historical case for the order of baptismal initiation first, followed by observance of the Lord’s Supper, which should be shared only among those who are baptized. Simply put, the historical innovation of inviting unbaptized believers to the fellowship of the Lord’s Table is a practice that must stop if we are to conform to the pattern established by the apostles and maintain the sacred rites of baptism and the Lord’s Supper in the manner in which they were given.

NOTE: Prior to presenting these arguments, I need to acknowledge that some of the discussion in this essay depends on understanding the multi-faceted role of baptism as articulated in my “Elephant” series here as well as the case for a weekly observance of the Lord’s Supper in my essay here. I would recommend reading those articles as a background to the arguments presented in this essay.

Biblical-Theological Considerations

Observance of the Lord’s Supper in the New Testament assumes the order of baptism into the visible body of Christ followed by the observance of the eucharist or communion as the gathered church. In 1 Corinthians 10:17, Paul says, “Because there is one bread, the many are one body, for the many partake from the one bread.” We partake together of the one bread (that is, breaking the one loaf into pieces and all partaking of the single loaf) because we are “one body,” that is, to visibly reinforce our confession of being “one body.”

Here the term sōma is not a reference to the physical body of Christ present in the bread, but the assembled church as the body of Christ, united as one corporate body in its gathering and symbolized by the partaking of the one bread. Thus, the participation in the observance of the bread is intended for those who are, in fact, united with the body, the church. We are united with the body through baptism (1 Cor. 12:12–13). Some have rebutted that this is “Spirit baptism,” not water baptism. Well, then, let them that are only baptized spiritually partake of the Lord’s Supper “spiritually,” and leave the physical elements alone. It is in any case best that we abandon this kind of dualism typical of ancient gnosticism in our approach to the church and sacraments and rather hold the spiritual and physical together in an incarnational theology. After all it, the church is called the body of Christ, not the soul or spirit of Christ. The physical-spiritual observance of the ordinance of bread and wine is for the church body gathered; an initiation and consecration into that church body is only accomplished by water baptism, a physical-spiritual act. I can see no logical way to make sense of Paul’s analogy of body unity through the supper in 1 Corinthians 10:17 except by assuming the participants have become members of the one body through baptismal initiation.

This “first-baptism-then-communion” order is also set forth in Paul’s typological treatment of Moses’s “baptism” and participation of the “manna” in the wilderness in 1 Corinthians 10, which “happened as examples (typoi) for us.” He says, “Our fathers were all under the cloud and all passed through the sea” (10:1). The cloud was the presence of God himself, the Shekinah glory. The sea, of course, was the Red Sea. He goes on: “All were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea” (10:2). The New Testament anti-type to Paul’s Old Testament type here is Spirit-baptism (cloud) and water baptism (sea). Just as the Old Covenant people of God were typologically “baptized” into Moses by the Spirit of the cloud and the water of the sea, New Covenant believers are baptized into Christ by Spirit-baptism and water-baptism. Note that they are not baptized into Christ by one or the other, or by one instead of the other, but necessarily by both held together in unity. Again, a biblical-theological view of the sacraments avoids dualism that separates the physical and spirit and pits one against the other or exalts one above the other. An authentically Christian view of the sacraments is incarnational, the spiritual and physical together without confusion or mixture and without separation or division.

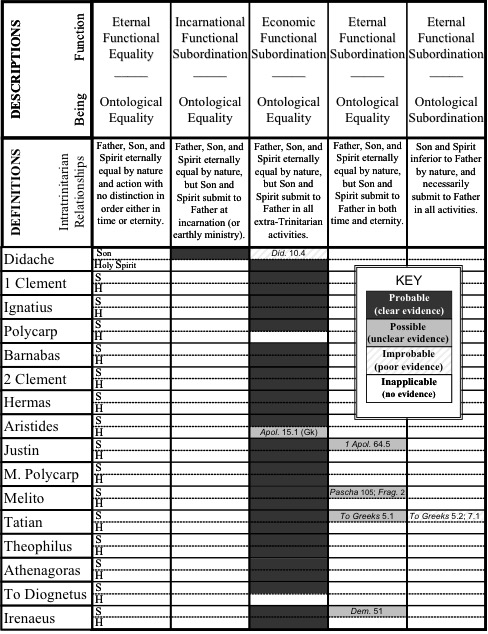

Then, in verses 3-4, Paul writes, “And all ate the same spiritual food; and all drank the same spiritual drink.” The New Testament anti-type of this Old Testament spiritual food and drink is the Lord’s Supper, which Paul is about to discuss in just a few verses in chapter 10 and then again in chapter 11. Thus, the context affirms this identification of the typology with baptism and the Lord’s Supper. The order is clear: Spirit-baptism (conversion) and water-baptism closely associated with it (see Heb. 10:22), then participation in spiritual food and drink (the Lord’s Supper). As a background confirmation of this analogy, the term “spiritual food and drink” is also used in the first-century Didache 10.1 in reference to the eucharistic observance. Therefore, reading Scripture in its actual historical context, Paul’s first-century readers of 1 Corinthians 10:3-4 would have understood his typology as an obvious reference to the spiritual corporate discipline of observing the Lord’s Supper, which came after (not before) baptism into Christ both by the Spirit and by water.

Also, the order of baptism and the Lord’s Supper in the narratives of Scripture is consistent. Christ said in the Great Commission, “Make disciples by baptizing them in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and [then] teaching them to observe whatsoever I have commanded” (Matt. 28:19–20). The Lord’s Supper, as an ordinance and command of Christ to be observed by the church as a sign of their corporate relationship to the New Covenant, is part of that which the baptized disciples are to observe. And in Acts 2, we read, “So then, those who had received his word were baptized; and that day there were added about three thousand souls” (2:41). Then, “they were continually devoting themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer” (2:42). Nowhere in Scripture is this order reversed.

Further, the biblical teaching concerning church discipline requires a baptized membership accountable to a baptismal pledge of repentance and discipleship. If a person has not actually committed to a life of discipleship and allegiance to Christ through baptism, how is it that the Lord holds them to such a commitment by disciplining those who partake of the Lord’s Supper unworthily (1 Cor. 11:27–34)? That is, a person is admitted to fellowship in the church body and charged with holding the faith and living the life of a consecrated disciple at baptism. (See here for a fuller explanation of baptism as a pledge to live the consecrated life.) Those baptized, consecrated believers are then the ones who are accountable to live lives that “judge the body rightly” (1 Cor. 11:29). The “body” here is not a reference to Christ’s physical body at the right hand of the Father, but a reference to church body united together by baptism. (See here for a fuller explanation of baptism as initiation into the covenant community of the church.) There is no room here for the participation of unbaptized (that is, non-consecrated, non-committed, and non-covenanted) professors of faith.

Besides this, we must note the correspondence of the language of 1 Corinthians 11:33—“when you come together to eat, wait for one another”; and 11:18—“when you come together as a church”; and 11:20—“when you meet together, it is not to eat the Lord’s Supper.” Clearly the “coming together” is a reference to the gathering of “the church,” which is, of course, the congregation of the baptized believers, members of the body through baptismal initiation. They are not merely those who have had a personal experience of faith or feel converted by their own personal standards; this conversion is confirmed by the church through proper training, testing, and then initiation by baptism. Only then is one counted a member of the church, the visible corporate body of Christ. And members of the church body, they gather with the church to eat the Lord’s Supper (11:18, 20, 33).

Biblically, the order is evident: first, baptism as the visible act of initiation into the new covenant community, second, the Lord’s Supper as the visible act of covenant renewal among members of the baptized community. Therefore, from the perspective of biblical-theological evidence, the burden of proof is on the person who would invite unbaptized believers to communion. The burden of proof is not on the person who requires that baptism be a pre-requisite for communion.

Historical Considerations

The first-century handbook for early church plants called the Didache (c. AD 50–70), instructs early church leaders regarding the proper practice of the eucharist (or “Lord’s Supper”) as follows: “But none shall eat or shall drink from your eucharist but those baptized in the name of the Lord” (Did. 9.5). This practice is in keeping with the pattern we see in the New Testament. This isn’t a case of early Christian legalism. This is the normal Christian practice of the early church (see Justin Martyr, 1 Apol. 66). It is in keeping with the establishment of the apostles and the logic that only those who have been initiated into the covenanted body of the church are to be admitted to the rite of covenant renewal that symbolizes the unity of that one body. Quite bluntly, to the early Christian, inviting an unbaptized believer to the Lord’s Supper would be like inviting an unmarried couple to the wedding bed! Having not entered into a covenant commitment to live a life of discipleship through baptism, why are they invited to the table where they are renewing that confession and commitment?

Historically, the order of baptismal initiation into the covenanted community followed by renewal of that covenant at communion has also been the universal practice of the church from the first century to the seventeenth. Even in Jonathan Edwards’ (17thcentury) disagreement with his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard, over who should be invited to the Lord’s Table, the issue was never whether unbaptized professors of faith should partake of the supper. Both men agreed that communion of the unbaptized was absurd; church membership and communion required baptism. Edwards wrote, “None should be admitted but such as were visibly regenerated, as well as baptized with outward baptism” (“Inquiry Concerning Qualification for Communion,” Part 2, Section 1.9). The issue was rather whether subsequent visible signs of genuine saving grace were necessary for baptized Christians prior to full church membership and thus participation in communion. Simply put, there would be no case in which a non-church member would be admitted to communion and there would be no case in which a non-baptized person would be admitted into church membership. In New England Congregationalism, being baptized as an infant did not guarantee full church membership, and neither did it guarantee participation at the table. But no unbaptized believer was ever admitted to communion. Such an allowance would be scandalous.

Among Baptists, who baptized only upon a profession of faith, a new issue began to surface. The practice of administering communion to those who were regarded by Baptists as “unbaptized” (that is, those baptized as infants) began with John Bunyan (17thcentury) and his circle. At the time, it was a controversial and, frankly, “progressive” practice. In 1814, Andrew Fuller, writing regarding Bunyan’s position, noted, “If Mr. Bunyan’s position be tenable, however, it is rather singular that it should have been so long undiscovered; for it does not appear that such a notion was ever advanced till he or his contemporaries advanced it. Whatever difference of opinion had subsisted among Christians concerning the mode and subjects of baptism, I have seen no evidence that baptism was considered by any one as unconnected with or unnecessary to the supper” (Andrew Fuller, The Admission of Unbaptized Persons to the Lord’s Supper Inconsistent with the New Testament: A Letter to a Friend [1814], 10-11).

Historically, the original and enduring practice—for centuries—has been baptism as the rite of initiation in the covenant community (whether paedo-baptism or credo-baptism) followed by the Lord’s Supper as the rite of covenant renewal. Only in the seventeenth century was the alternative perspective seriously considered by some. Since then, this progressive novelty has spread especially among independent evangelical churches. Therefore, from the perspective of historical evidence, the burden of proof is on the person who would invite unbaptized believers to communion. The burden of proof is not on the person who requires that baptism be a pre-requisite for communion.

Conclusion: No, Unbaptized Believers Should Not Be Invited to the Lord’s Table

It is not right nor safe for churches to invite the unbaptized to the table. No pastor, board of elders, denominational authority, Bible scholar, or professor of theology has the authority to undo what the apostles established and what churches practiced for sixteen centuries. And leaving the decision up to the individual is no solution. It makes no sense to relinquish pastoral responsibility over the proper admission to the table and rather to give this authority to the individual or the family to decide. In so doing, how are we not corporately failing to “discern the body”?

This is a serious matter, as both baptism and the Lord’s Supper are solemn, covenantal acts. The Lord’s Supper is not a point of personal devotion, but a point of corporate covenant renewal. And by “corporate” I mean the gathered visible body of Christ—the church established as such by baptism.

The biblical, theological, and historical facts place the burden of proof on the person who would invite unbaptized believers to communion. The burden of proof is not on the person who requires that baptism be a pre-requisite for communion. That is, the default position should be the requirement of baptism for participation in the Lord’s Supper; any differing practice must meet the burden of proof to demonstrate biblically, historically, theologically, and practically how deviating from this conservative position is proper and permissible.