A man once asked a famous nineteenth century preacher to weigh in on a controversial doctrinal issue that has divided Christians for centuries: “What do you hold concerning water baptism?”

A man once asked a famous nineteenth century preacher to weigh in on a controversial doctrinal issue that has divided Christians for centuries: “What do you hold concerning water baptism?”

The preacher responded evasively: “My mouth.”

Another issue today evokes the same urge to keep our traps shut: the ordination of women to pastoral ministry. For some denominations this matter was settled generations ago either for or against. For others the issue flares up periodically, unable to be finally resolved. Frankly, in some circles it’s simply not prudent or polite to even discuss this topic, because whatever one might hold concerning the ordination of women will inevitably cross somebody’s strongly-held beliefs. This has led many to simply hold their mouths whenever the question comes up.

Too often, an honest, fair, and civil discussion becomes difficult. Misogynists (men who hate women) will universally seek to limit the role of women in ministry, but limiting the role of women isn’t necessarily misogyny. Similarly, feminists will universally seek to expand the role of women in church ministry, but expanding the role of women is not itself feminism. (“All A = B” does not imply “All B = A”) Yet all too frequently those engaged in the debate over the biblical, theological, and historical understanding of the roles of men and women in ministry can’t separate facts from emotions or analysis from implications.

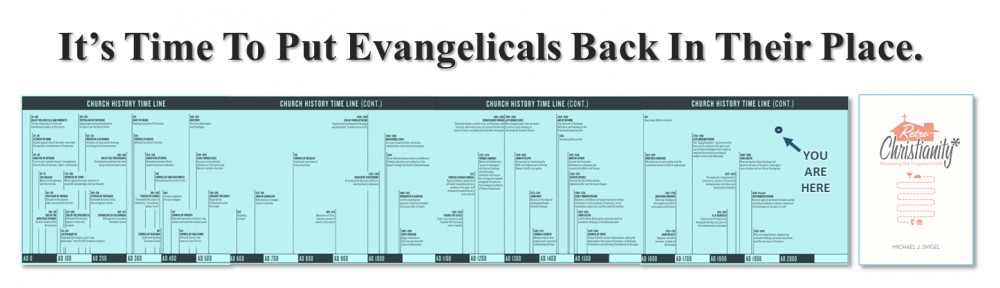

The following essay doesn’t presume to settle the question of women in ministry, and we can’t promise not to stir up strongly held emotions from either side of the debate. However, we do seek to contribute modestly to the discussion by asking the question, “Did the apostles establish the office of deaconess?” We seek to answer this through both biblical and historical lines of argument, seeking to read the Scriptures in a way that’s faithful to the text but also consistent with the historical-theological context. That is, what do we know about the actual practices of the early churches established by the apostles, and how does this picture affect the historical context in which we should read the apostles’ writings? [For a more comprehensive application of this historical-theological approach to New Testament interpretation regarding important issues related to the church, see Michael J. Svigel, RetroChristianity: Reclaiming the Forgotten Faith (Crossway, 2012).]

The Language of “Deacons”

In order to address the question of the potential presence and particular role of deaconesses in the apostolic era (the time period of the apostles and their disciples), a couple of things need to be understood about the nature of a “deacon.” The Greek word itself, diakonos, has a fairly broad range of meaning, such as “a generic servant,” “a waiter of food,” “an agent with a special mission,” or “an official minister in a church.” In the New Testament diakonos can mean a servant with a certain mission or task (Rom. 15:8; 1 Cor. 3:5; Eph. 3:7); an assistant of a particular person (Matt. 22:13; 2 Cor. 6:4; Col. 1:7); or an official appointment, office, or position as a “minister” in a local church (Phil. 1:1; 1 Tim. 3:8–12).

Though all people were called to be diakonoi (servants), when Paul couples this title with the words for “elders” (presbyteroi) and “overseers” (episkopoi), he appears to use diakonos as an official title—a title that soon took on the sense of a distinct rank in church order (the diaconate) and still remains with us today in most ecclesiastical traditions as “deacons.” In fact, the present distinction between the general calling of all believers to serve and the specific “office” within church governance is so clear that the former are simply called “servers,” “helpers,” or “volunteers,” while the latter are called “deacons” or “ministers.” In Paul’s day the vocabulary itself was the same for both the general and the official: diakonos.

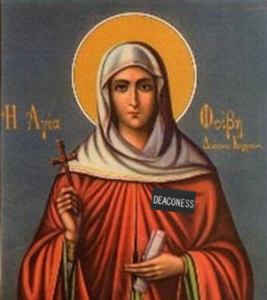

What does this technical discussion of the word “deacon” have to do with the issue of women holding ordained ministerial offices in the church? Well, in two New Testament passages it appears that the term diakonos in the official sense applies to women. In 1 Timothy 3:11 the context may include both men and women “deacons,” while Romans 16:1 refers to a specific woman, Phoebe, as a diakonos. Though these passages have been interpreted in different ways, we contend that when read in light of the early church’s actual practice of appointing deaconesses, the evidence for understanding these passages as referring to official “deaconesses” tips the balance away from alternative interpretations.

Phoebe—Servant, Assistant, or Minister (Romans 16:1)?

A greatly contested passage regarding the presence of official deaconesses in the apostolic age is Paul’s commendation of Phoebe (a woman) as a diakonos: “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a servant (diakonos) of the church at Cenchreae, that you may welcome her in the Lord in a way worthy of the saints, and help her in whatever she may need from you, for she has been a patron of many and of myself as well” (Rom. 16:1–2, ESV). On this occasion, Phoebe had been appointed to a specific task—that of bearing the letter to Rome on Paul’s behalf. But does her designation as diakonos go beyond her task as Paul’s agent and messenger?

Interpreters who understand the term diakonos to mean a general “servant” from Cencreae rather than an official “deaconess” often argue that the term was ascribed to other individuals who were not regarded as filling the office of “deacon” in their churches, such as Paul (Eph. 3:7), Epaphras (Col. 1:7), Tychicus (Eph. 6:21), Apollos (1 Cor. 3:5–6), and even Timothy (1 Tim. 4:6). True, Paul could merely be placing Phoebe into the same general category of “helpful servant” as these other men, but this overlooks the two following important facts.

First, Paul describes Phoebe as a “diakonos of the church at Cenchreae,” specifying her function as diakonos to that specific church. This may seem insignificant until we realize that whenever the Greek phrase “________ of the church” is used in the New Testament and the earliest Christian literature (where “________” is a personal designation or title), the personal designation refers to an office, not just a generic function (Acts 20:17; Eph. 5:23; Jas. 5:14; Rev. 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14; Ignatius, Trallians 2.3; Philadelphians 5.1; Polycarp 1.1; Shepherd of Hermas, Vision 2.2.6; 2.4.3; 3.9.7; Martyrdom of Polycarp 16.2; 19.2). Therefore, if Phoebe is merely a “helpful assistant” of the church at Cenchreae in Romans 16:1, this is the only time the construction is used this way in the earliest Christian literature.

Second, in Romans 16:2 Paul describes Phoebe as “a patron (prostatis) of many and of myself as well.” The word prostatis means “helper,” or “benefactor.” In this way Paul describes Phoebe’s general function as an assistant with a “servant’s heart.” If he generalizes her service to “many” in verse 2, it seems more likely that her particular function as “diakonos of the church” in verse 1 had a more specific and official sense. Verse 1 identifies Phoebe and her official office in her home church (a deaconess), while verse 2 describes her character as a general servant beyond her local church.

Of course, when we call Phoebe a “deaconess” we must recognize that the actual responsibilities and authority associated with titles like elder, pastor, teacher, and deacon in the early church were still in the formative stages. New Testament scholar Douglas Moo writes, “It is very likely that regular offices in local Christian churches were still in the process of being established, as people who regularly ministered in a certain way were gradually recognized officially by the congregation and given a regular title” (Moo, Epistle to the Romans, 914).

Even if Phoebe is called a diakonos in a quasi-official sense, the actual meaning of the term could still be floating somewhere between “servant-hearted helper” and “official church minister.” However, it may also be that the official recognition and designation of the office of “deaconess” began to develop early in the apostolic period. After all, the church had already been established for about twenty-five years, and several titled offices had been well-known in the churches from the beginning (Acts 1:20; 11:30; 14:23; Phil. 1:2).

Deaconesses or Wives (1 Timothy 3:11)?

The second passage we need to consider closely is the mention of the gynaikes (“women” or “wives”) in the context of the qualifications for deacons in 1 Timothy 3:11. Some understand the word to refer to the wives of the official deacons described in verses 8–10 and 12–13. That is, the men who fill the office of deacon should have “wives” (gynaikes) that are dignified, slanderer-free, sober-minded, and faithful (3:11).

It should be noted, however, that the word “their” often inserted in many English translations is not in the original Greek text. The Greek simply says, “gynaikes likewise.” It’s the same construction Paul used in verse 8 when he transitioned from the qualifications for elders to the qualifications for deacons: “Deacons likewise” (1 Tim. 3:8). This implies a “distinct, though similar, group” (I. Howard Marshall, The Pastoral Epistles, 493). Also, if Paul wanted to clearly refer to the wives of the deacons, he could easily have inserted the possessive pronoun to indicate this, saying “their wives” rather than the simple generic word for “women.”

Yet some might object that Paul immediately returns to the obviously male deacons in the next verses (12–13), where deacons are to be “the husband of one wife,” suggesting that verse 11 was simply an aside to describe the character of the deacons’ wives. However, it seems that if deacons’ wives were really in view, Paul would have inserted the parenthetical statement after actually mentioning the “one wife” of each deacon in verse 12. Instead, it seems most reasonable that Paul mentioned the “women” in verse 11 (that is, “female deacons”) before mentioning that the male deacons could have one wife in verse 12 in order to avoid the identification of the women in verse 11 with the wives of the deacons in verse 12.

Another problem with the “wives of deacons” interpretation of verse 11 is that Paul makes no mention of the character traits expected of the wives of overseers, though he clearly mentions they were permitted to have “one wife” (1 Tim. 3:2). So, are we to conclude that the character of deacons’ wives was more important and needed special mention? Were deacons’ wives more likely to be undignified slanderers? Paul doesn’t mention the ideal character qualities of elders’ wives in Titus 1:5–9, either, making us wonder why he suddenly mentioned the virtuous qualities of deacons’ wives in 1 Timothy 3:11. However, if we interpret this text as referring to qualities expected of the female deacons or “deaconesses,” then the problem resolves itself.

Of course, the evidence here is far from crystal clear. Coupled with Romans 16:1, the sudden appearance of the “women” in the midst of qualifications for deacons in 1 Timothy 3:11 seems to strengthen the possibility that the apostles had appointed both male and female deacons in the local churches. However, we must leave this possible reading of the biblical evidence and approach the question from another direction: the historical context of the early church.

Did the Apostles Leave the Early Church with Deaconesses?

Several historical arguments support the claim that deaconesses were, in fact, present and functioning in an official capacity in the early church—so early that it seems most reasonable that both men and women were among the original appointees to the general office of diakonos. In a section of an early Christian writing, Shepherd of Hermas (Vision 2.4.3), the leader of the church in Rome, Clement, is being commissioned to share the author’s message with those outside the city: “And you will write two books, and send one to Clement and one to Grapte. Clement will send it to the foreign cities, because it is permitted to him so to do, but Grapte will admonish the widows and orphans.” Early testimony informs us that a man named “Clement” was a prominent leader of the church of Rome in the late 90s—at the twilight of the apostolic era. One of his responsibilities at that time was to correspond with other churches. At the same time, Grapte (a female) was tasked with instructing “widows and orphans.” Later in the Shepherd of Hermas, we learn that looking after the widows was a responsibility given to the “deacons” (Similitude 9.26.2). Thus, at the very end of the apostolic period we have historical evidence of a female deacon, Grapte, functioning in an official capacity in a prominent church (Rome).

A second early testimony of the presence of deaconesses comes from a different region of the church: Asia Minor. Around 111 C.E. (a decade after the apostolic period), a Roman governor, Pliny the Younger, wrote a famous letter to the emperor Trajan (Lib. 10.96, Plinius Traiano Imperatori). In this letter Pliny consulted the emperor regarding the punishment of Christians, the beliefs and practices of whom Pliny had investigated. He learned details of Christian beliefs and worship by capturing and torturing two female Christians called ministra in Latin, a translation of the Greek “deaconess.” Thus, shortly after the end of the apostolic period we have additional historical evidence of female deacons in Asia Minor.

A third historical testimony relates to the practical need for women to assist the elders in the baptism of female converts to Christianity—filling a role parallel to male deacons for the baptism of men. In the daily ministries of the church, women were expected to minister to other women, especially when a home visit was required. This is attested in the third century Didascalia, which itself is based on earlier second century writings. That document urges “deaconesses” to minister to women in their homes, as it would be inappropriate for male deacons to do so (Didascalia 16). Likewise, both male deacons and female deaconesses were necessary for baptizing men and women in the early church, especially since they were baptized naked (Hippolytus, On the Apostolic Tradition 21.3, 5, 11). Thus, deaconesses would have been needed to assist in the baptism of women, just as male deacons assisted in the baptism of men. In short, the practical everyday needs of the Christian community strongly suggest that the early church would have required women ordained to a position in the church equal to that of deacons in order to minister to women in contexts that would have been impossible for men.

Finally, the transition from the apostolic period with both male prophets and prophetesses to the post-apostolic period leads to a strong possibility that just as temporary apostles were replaced by permanent elders (functioning as evangelists, pastors, or teachers), the prophets and prophetesses would naturally have been replaced by the deacons and deaconesses. Already during the New Testament period the church had women ministering in church as prophetesses (Acts 21:9; 1 Cor. 11:5). It may be that the temporary first century role of the prophet, which was an office in the church occupied by both men and women, was replaced by the office of deacons, occupied by both men and women. This would create a consistency in transitioning from the apostolic period to post-apostolic period, when apostles were replaced by the pastoring and teaching elders while the prophets and prophetesses were replaced by the ministering and serving deacons and deaconesses by the beginning of the second century.

Conclusion: Summary of the Arguments

Clearly, both Scripture and the ancient church point to an incontestable fact: women were heavily involved in the ministry of the church both local and catholic. Exactly when the function of recognized “servants” of the church—both male and female—began to be identified as an actual office of “deacon” or “minister” is not so clear. Though it’s possible that the office of deaconess was established from the very beginning, it’s also possible that this office grew into its own over the course of the apostolic period (A.D. 35–100).

Already in the 50s, Phoebe was singled out for her patronage. She had helped Paul on more than one occasion (Rom. 16:2) and most likely carried his letter to the Romans. Around A.D. 65, Paul described the necessary qualities for “women” in the context of qualification for deacons (1 Tim. 3:11). In Rome around A.D. 95 a woman named Grapte was told to minister to “widows and orphans” by teaching them—a task assigned to those in the deaconate. Around A.D 110 two women ministra (“ministers”/“deacons”) were described as suffering for their faith in Asia Minor. As the second century progresses, we see female deacons assisting the elders in the work of the ministry, teaching, caring for, and even assisting in the baptism of women and children.

What does this evidence suggest? It suggests that by the end of the apostolic age the ordained church office of “deaconess” was in existence, having developed throughout the apostolic period and therefore endorsed by apostolic authority. This is by no means a case that can be demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt, but the available evidence seems to tip the balance toward the establishment of an office for “deaconesses” as a biblical office. Such an office would involve training, testing, and ordination to this particular appointment. It would also involve real authority and responsibility as deacons and deaconesses worked together in assisting the elders in the work of church ministry, granted the title of “ministers.” In short, a truly “conservative” approach to the role of women in ministry that seeks to base their churches on the most likely post-apostolic model would include not only male but also female ministers assisting the elders in the work of the ministry.

However, a few caveats are in order. First, although there appears to us to be substantial evidence in the New Testament and early church for the presence of deaconesses in the churches, there is no evidence for the presence of female elders or pastors. Therefore, a modern iteration of this post-apostolic order would be composed of male pastor-elders assisted in the ministry by both male and female ministers.

Second, the role of deaconesses appears to have been limited to the care of widows and orphans—women and children, but it seemed to have included their catechetical instruction, baptism, and discipleship—all under the oversight of the church elders. Similarly, the role of male deacons was also generally limited to the catechesis, baptism, and discipleship of men. Therefore, a modern iteration of this post-apostolic order would involve ordained women ministers primarily focused on the women’s and children’s ministry.

Third, early churches appear to have exercised some sensibility regarding the compatibility between a woman’s “stage of life” and her responsibilities for church ministry. Married women in child-rearing years do not appear to have been primary candidates as deaconesses, who tended to be older women—often widows—who in any case had enough time and energy to commit to full-time Christian service. Similarly, unmarried women (“virgins”) also engaged in official ministry as “deaconesses.”

[This essay was researched and co-written by Michael J. Svigel and Kymberli Cook. Originally posted at http://www.retrochristianity.org on April 14, 2012.]